Samira is a Year 8 student whose KS2 SATs scores were just shy of the national average. As they meet the nationally expected standard for English and maths, a casual observer may conclude that she is not a student of concern.

It’s an impression that would only be reinforced by her mean CAT4 score, which is above average and which again suggests that Samira doesn’t find school particularly challenging. She seems bright and alert and is, all in all, a well-behaved, conscientious student.

Yet her teachers have noticed that while her exam results are unspectacular, Samira has some notable skills. To the astonishment of her friends, she can complete a Rubik’s Cube in 30 seconds. To the surprise of her teachers, she can become so engrossed in practical projects that she skips lunch and stays on after school to work on them. She also loves coding and creates complex and interesting games in Python in her spare time.

Written and oral assignments are a different matter, though. Although Samira generally completes these moderately well, she tends to find tasks that depend on verbal ability more challenging.

Spatial thinkers such as Samira think initially in images before converting them into words. They tend to have good visual imaginations and usually are adept at working with mind maps, diagrams, pictures or 3D images.

Higher spatial skills

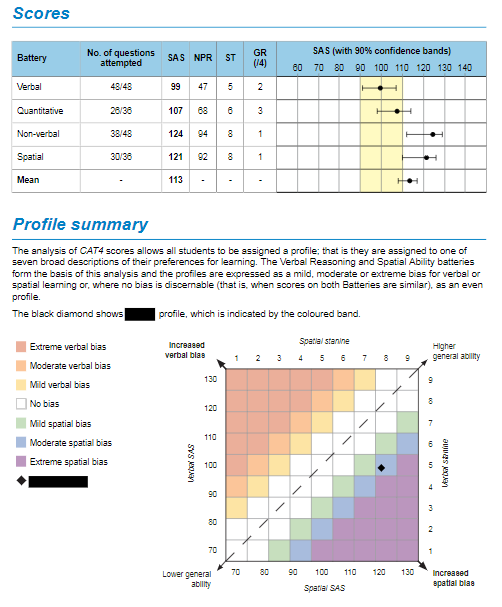

Samira is one of the estimated 7% of children in the school population who have relatively much higher spatial skills compared with their verbal abilities (a difference of three or more Stanines) – the equivalent of 56,000 children in each year group in the UK.

Like many such children, she finds a curriculum that puts a premium on language skills more of a struggle than the rest of her peers. Moreover, her spatial and non-verbal abilities are so high that they have inflated her mean CAT4 score. This may lead teachers not only to underestimate just how challenging Samira finds the text-heavy curriculum, but also to overestimate how she will perform academically. And as Samira doesn’t find communication as easy, she may struggle to explain when she encounters a problem or what exactly she is feeling.

Spatial thinkers such as Samira think initially in images before converting them into words. They tend to have good visual imaginations and usually are adept at working with mind maps, diagrams, pictures or 3D images.

Spatial thinkers often turn out to be good at STEM subjects, coding, game creation and design. One of the most interesting findings from a huge survey of 400,000 students carried out in the US over 50 years was that youngsters who scored highly in spatial tests were much more likely to study STEM subjects at university and go on to be scientists and engineers.1

Unfortunately, though, their talents are often unseen. Most assessments don’t include any spatial measures and the high verbal bias of much of the curriculum only serves to mask much of this hidden potential.

“CAT4 is one of the few formative assessments to test for spatial abilities and capable of identifying non-verbal talent,” says Ian Mooney, Strategic Lead on Partnerships and Assessment at the Northern Schools Trust. “As high spatial ability is increasingly recognised as a reliable indicator of later success in STEM subjects and in fields such as design and engineering, it should be more widely identified and appreciated.”

As high spatial ability is increasingly recognised as a reliable indicator of later success in STEM subjects and in fields such as design and engineering, it should be more widely identified and appreciated.

Ian Mooney, Strategic Lead on Partnerships and Assessment at the Northern Schools Trust

Samira’s score and profile summary

Samira scored highly in both non-verbal reasoning and spatial ability, less well in quantitative ability and verbal reasoning. She has a preference for spatial over verbal learning and is likely to respond well to active learning methods, such as modelling and simulations. Her learning profile is represented by the black diamond mid table opposite.

Students like Samira tend to be as unconfident vocally as they are with the written word, which means they can struggle to make an impression in class or contribute to discussions. And while they are often ‘intuitive’ and capable of seeing the big picture, it can be at the expense of attention to detail.

She should do well in subjects such as science, technology and design, but might find subjects like English Literature and History more challenging – and even Biology and Maths, too, given their high use of written language.

Samira’s teaching and learning needs

If Samira’s spatial bias is recognised and appropriate measures taken to build on it, Samira could make real progress in STEM and design subjects. However, it’s essential that she is given the tools to boost her verbal skills in order to enable her to access a text-dependent curriculum and that she is encouraged to develop her verbal skills.

Her teachers should therefore:

- Set her challenges involving active learning methods, such as simulations, problem-solving tasks and the creation of original ideas, particularly those involving imagery;

- Use techniques that will quickly engage her, such as pairing verbal materials with written compositions where possible;

- Involve Samira in group work, where she can learn from the verbal skills of others and demonstrate her ability to visualise a solution, see a pattern or draw conclusions from disparate sources;

- Encourage her to explain her understanding of spatial activities and to reflect critically on them;

- Address her verbal weaknesses with targeted interventions and expose her to a broad range of materials to engage her interest;

- Help her understand the importance of mastering English and maths. Even if she chooses a career in coding or engineering, she’ll need to master these skills to be able to promote herself and her work.

CAT4 is one of the few formative assessments to test for spatial abilities and capable of identifying non-verbal talent.

Ian Mooney, Strategic Lead on Partnerships and Assessment at the Northern Schools Trust

- Project Talent longitudinal study, conducted on 440,000 American high school students by American Institutes for Research from 1960 onwards

Talk to our specialists

If you would like to speak to one of our specialists about how we can support your students taking the big step into a new school, add your details to our form and we’ll get in touch

Find out more about our transition assessments

Quickly securing a sound transition into secondary school is vital in ensuring students go on to achieve their potential at school, in GCSEs and beyond. Find out how our assessments can help.